Setting foot in Bengaluru is like stepping into a future India. The city is quickly becoming one of the most important cities in the Indo-Pacific region, and it’s time New Zealand took note.

Dubbed the Silicon Valley of India, Bengaluru (previously Bangalore) is home to multinational tech giants like Apple, and Microsoft, with plenty of homegrown startups. Not to mention New Zealand heavyweight Fisher and Paykel Healthcare. The city’s maintains a deep well of technological talent matched with an entrepreneurial pulse.

The Vidhana Soudha, the state legislature of Karnataka. Photo: Jack Marshall

I’m writing to you sitting in my new apartment in Bengaluru. For the next three months, I'll be working at The Deccan Herald, one of India’s largest English newspapers. Supported by the Asia New Zealand Foundation, I chose to intern in India because I imagine this is what China felt like twenty years ago: On the cusp of being a great power.

In the early 2000s, Bengaluru’s population hovered around 5 million. Today it boasts at least 12 million residents after decades of relentless growth. In the often hot and humid subcontinent, the ever-pleasant climate in the cosmopolitan southern capital is a slice of heaven. Then you step off the plane at Kempegowda International Airport, and the intensity of the development hits.

The international terminal is new, solar-powered and lush with greenery. Outside the airport is a towering 33-meter-high statue of Bengaluru’s founder father Kempe Gowda (1510 - 1569), completed in 2022. But it’s on the long taxi ride into the city when the real development becomes apparent.

The author enjoying an affordable cup of coffee. Photo: Jack Marshall

Some 30 meters above the streets for 58 kilometres, a high-speed rail connection from the airport to the city centre is being built at pace. From my taxi, I could see men working on the project at midnight as my driver weaved through traffic and asked me about the Black Caps.

Development is making Bengaluru a modern city, which like any modern city, has translated into an obsession with cafes and craft beer. Bengaluru is dotted with brewpubs throughout the city, with each pub proudly showing off its brew kettles and tanks full of house-made beer. The manager of ShakesBierre brewpub told me they only import Belgian hops for their beers.

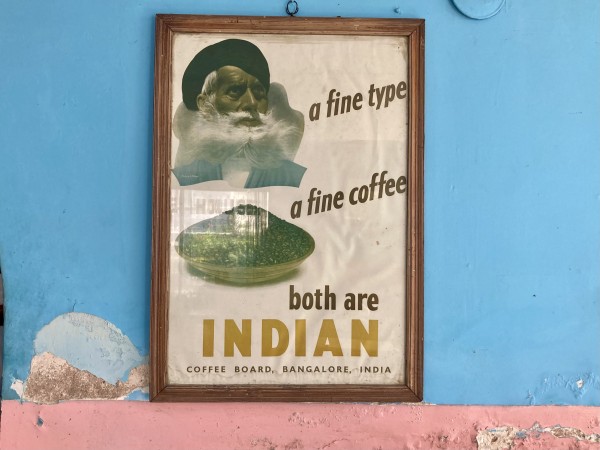

As for coffee, the city has a rich history of producing and drinking coffee. Old-school coffee houses still serve cups of coffee at exceedingly affordable prices, with a new generation of Melbourne-esque cafes now peppered through the city. All the buzzwords are here: Single origin this, Arabica beans that.

A vintage poster inside Indian Coffee House, a cooperative-run cafe since 1957. Photo: Jack Marshall

India’s growth is intensely exciting, yet not all is rosy in the subcontinent. Indian author and columnist Chetan Bhagat argues India maintains an unhealthy cultural hierarchy where the powerful and wealthy are celebrated for their position rather than actions.

This is partly to blame for the ongoing corruption, he says. In his book, What Young India Wants, Bhagat says India lacks effective laws to prosecute blatantly corrupt practices like insider trading.

“Many may not even see insider trading as wrong— We see it as a privilege of being in a position of status or power.”

This goes extra for politicians. India’s Supreme Court granted legislators immunity in bribery cases in 1998. The ruling came after five ministers were charged with accepting bribes to vote a certain way during a vote of no-confidence against the government. In a positive step, just this month, the Supreme Court overturned that ruling.

Outside Bengaluru airport passengers are greeted by a 33-meter statue of Kempe Gowda, the founder of Bengaluru. Photo: Prime Minister's Office of India

Bengaluru, like the rest of India, has a distinctly youthful vibe for an obvious reason: The Indian population is young. With the world’s largest population at 1.5 billion, the median age of an Indian is around 28 years old. By comparison, the median age is 38 in the United States and 39 in China. The Pew Research Center says people under the age of 25 account for more than 40% of India’s population.

Now let this sink in: The Centre says there are so many Indians in this age group “that roughly one-in-five people globally who are under the age of 25 live in India.”

Business leaders and policymakers should pay attention to that. New Zealand has long relied on China as its largest trading partner, which accounts for 27% of its exports, but that may soon change. Unlike India, China is experiencing a rapidly ageing population because of its one-child policy. India’s population is young and growing.

This is where Bengaluru comes in. Being the tech capital of India, it is experiencing enormous growth in industries that New Zealand could benefit from. Despite its location in a developing nation, the tech-savvy city is leapfrogging New Zealand in many ways because of its laser focus on tech.

Although Bengaluru is moving towards modernity there’s plenty of messy wiring to organise. Photo: Jack Marshall

Already the city is employing artificial intelligence in its traffic management, delivery and payment services. It can do so because it hosts some of the best computer engineers who work at the world’s best tech companies.

But forging trade deals with India will be very different from our successful negotiations with China for three key reasons.

First, India is a democracy divided across 28 states and eight union territories, each with their own wants and needs. In China, there is little debate once the government decides on a course of action.

Second, India has a long history of protectionism, with high tariffs and a general suspicion towards outside companies taking over (Remember the East India Trading Company?).

India is very proud of its military. You’ll find tanks and warplanes displayed in many cities. Photo: Jack Marshall

Third, and most importantly, the dairy problem. India’s rural population depends on its agricultural industry for economic and physical sustenance. A free trade deal including dairy is politically unpalatable.

Chief Executive at the Asia New Zealand Foundation Suzannah Jessep argues we need a mindset change. Jessep says focusing only on export trade is shortsighted and unlikely to bear fruit. Instead, we must rethink how India and New Zealand can forge closer ties through other avenues.

Collaboration with India is a surefire way to get interest from regular Indians and their politicians. As Jessep argues, making people-to-people connections will “foster greater levels of trust, understanding and mutual respect and that — ironically — might ultimately prove to be the necessary ingredients to forge a deeper, closer trade relationship in the fullness of time.”

Banner image: satyaprakash kumawat on Unsplash

- Asia Media Centre